ORCAS

The top predators of the world’s oceans. Great places to meet them are Norway, Iceland and Canada.

Photo: Oliver Dirr / Whaletrips

REVIEW: ORCAS

Killer whales are the smartest and most dangerous hunters of the seas – this combination is probably what makes watching them in the wild so fascinating and impressive. You automatically have a tremendous amount of respect.

Apart from humans, orcas have no enemies anywhere. They are the top predators in the world's oceans and are at the very top of the food chain. Worldwide. If the Arctic ice continues to recede and polar bears are forced to spend even more time in the water, orcas could even become a threat to them, the largest and strongest predators on land.

Early whalers gave orcas the name "killer whale". Because they seemed to attack and kill all other animals, even the largest whales. Even the whalers were afraid of orcas. Wrongly so, because to date not a single attack on humans has been documented in the wild. Orcas only appear to be dangerous to humans when they are separated from their family and locked up in an aquarium for years.

Orcas live in stable family groups that stay together for life – children, grandchildren, grandparents, aunts. These families are called schools or pods. At times, several related schools come together and form large clans of up to 150 animals. These clans even develop their own dialects and hunting habits, which allow them to be clearly distinguished from one another.

Individual clans seem to specialise in a certain type of prey – fish, seals, whales – other possible prey is then even ignored. Several pods often co-operate in the hunt, and sometimes other whales join in for a short time, apparently without any fear. The hunting strategies of orcas are extremely variable:

In Norway and Iceland, orcas herd schools of herring into a large ball, which they constantly circle or enclose with a wall of air bubbles. They then stun individual fish with a flick of their fluke and pick them out.

“The various hunting techniques of orcas differ from clan to clan, as do the dialects, and are passed on within the families to the next generation – which can very well be described as culture.”

Some orcas in North America are specialised on seals and sea lions, which they sometimes hit through the air like a tennis ball with their flukes. In South America, some orcas deliberately beach themselves in order to surprise young sea lions on the beach, hidden by the surf, and then get pulled back into the sea by the next wave.

In polar regions, orcas can be seen breaking up ice floes on which they have spotted sea lions or penguins while scouting. If the ice floe is small enough, several orcas swim towards it in a group, dive in a coordinated manner and create a bow wave that washes the victim down. Young orcas have also been observed repeating this technique several times and repeatedly allowing their victim to escape back onto the ice floe – apparently deliberately, in order to continue practising their hunting technique.

When hunting large whales, on the other hand, orcas act like a pack of wolves: they chase their victim to exhaustion, attack from all sides, prevent the whale from diving from below and from taking a breath from above.

Attacks on great white sharks have even been observed off California – without any chance for the shark: orcas attack in a coordinated manner from several directions and stun the shark with targeted thrusts and blows with their flukes. A fight of only a few seconds.

The various hunting techniques differ from clan to clan, as do the dialects, and are passed on to the next generation within the families – which can very well be described as culture.

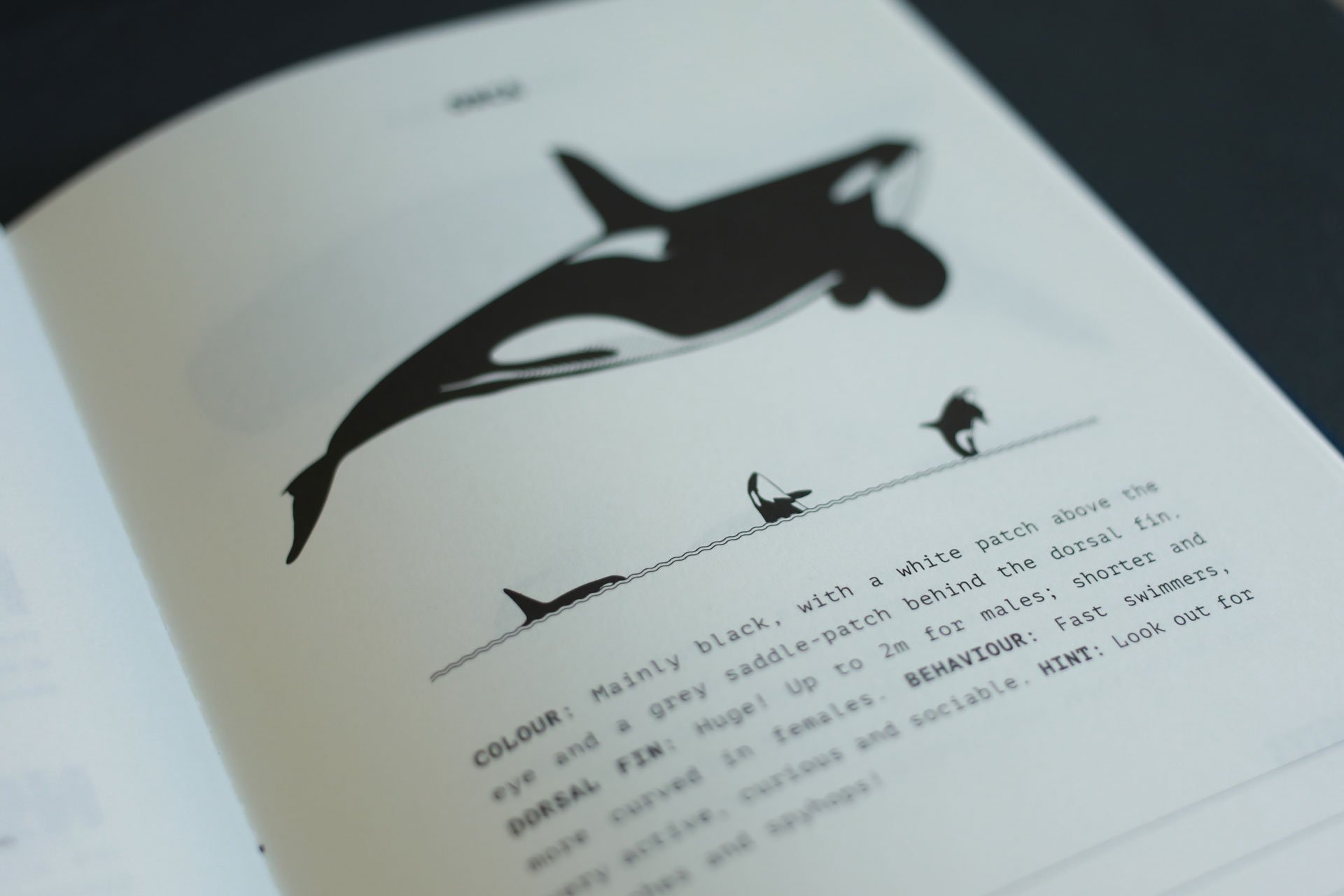

Male orcas can be recognised by their huge upright dorsal fin. In females, it is significantly smaller and curved.

In British Columbia (Canada) it has been discovered that there are resident and non-resident populations (residents and transients), far from the coasts there is also a third group (offshores), and off Chile even a fourth orca type was recently discovered that is clearly different from all the others.

The groups sometimes differ greatly. Residents migrate on mostly predictable routes, live together in larger groups, are much more communicative and usually feed on fish. Transients migrate longer distances on barely predictable routes, live in smaller groups, are less communicative and mostly feed on mammals. Little is known about offshores, nor about the Chilean subspecies.

Orcas are communicative, sociable, intelligent animals – they can even recognise themselves in the mirror and therefore clearly have a sense of self. Although orcas are actually dolphins and are usually viewed as whales only because of their size, they are without question by far the most impressive whales of all.

Photo: Oliver Dirr / Whaletrips

Size

Males grow from 5 to 9 metres, females from 4 to 7 metres. They weigh a maximum of 10 tonnes.

Colour

Black. White spot above the eye, grey-white spot under the fin, white on the underside.

FORM

Heavy, massive body with tall fin and paddle-shaped flippers. Tail rather narrow.

Blow

Low, bushy blow (1 to 2 metres), not always easy to see, but can clearly be heard.

Fin

Huge fin, up to 2 metres in males, sits upright and in the middle. Smaller and crescent-shaped in females.

FLUKE

Upper side black, underside light to white. Convexly curved, with a clear notch in the centre.

Behaviour

Curious, orcas often breach and spy-hop. They like to approach boats and occasionally accompany them.

Dives

No longer diving times, usually only 1 to 3 minutes and very steady on the surface.

Numbers

Orcas are widespread and can be found in all oceans. There are probably around 50,000 animals worldwide.

Photo: Oliver Dirr / Whaletrips

CHECKLIST: ORCAS

Killer whales often form schools of up to 25 animals. They are usually quite active on the surface.

When migrating, orcas usually travel at speeds of up to 10 kilometres per hour, and significantly faster when hunting; speeds of up to 54 kilometres per hour have been measured.

Residents usually form schools of 5 to 25 animals, whose dive sequence usually follows a fixed pattern – they dive 3 to 4 times at intervals of 10 to 30 seconds, followed by a longer dive of 3 to 4 minutes. Their routes are quite predictable.

Transients, on the other hand, travel in smaller groups and are often underwater for up to 15 minutes. They often change direction, which makes it difficult to predict where they will surface next.

“When spy-hopping, orcas emerge so far out of the water that even the flippers become visible. In this way, the animals try to orientate – they can see almost as far above water as humans.”

Both adults and juveniles often breach with an elegant, often sideways leap in which the entire body is lifted out of the water. They then land on their back, belly or side with a loud splash.

Spy-hopping can also often be observed, with orcas getting so far out of the water that even the flippers become visible. Several animals often spy-hop at the same time. In this way, the animals try to orientate – above water, they can see almost as far as humans.

Individual orcas can be identified very easily based on their fins and colour patterns, as well as the composition of the group, so you should be able to get a lot of information about the spotted animals directly on the boat.

Photo: Oliver Dirr / Whaletrips

Where and When: OrcaS

Although killer whales are found in all the world's oceans, there are not too many places in the world where they can be reliably observed.

Orcas live in all the world's oceans and are one of the most widespread mammals in the world. However, they prefer to stay in cold polar rather than sub-tropical waters. The routes of the residents are easy to predict, but those of the transients are still quite unknown. Although killer whales are so widespread, there are not an unlimited number of places where they can be observed easily and reliably:

In winter, you have very good chances in the north of Norway (from Tromsø northwards) when the herring gathers in large numbers in the fjords. From November to February, large numbers of residents can be found here very reliably. From spring onwards, however, the herring spread out in all directions – as do the orcas. Orcas can also be encountered off the coast of Andenes independently of the herring, as there are groups living here that are specialised on seals.

The ideal companion for your next whale trip: In our shop you will find our TRAVEL NOTES in five great colours – with the most important whale information for your trip and plenty of space for your own notes, observations and memories. Order now!

During the summer, the best chances are along the coasts of British Columbia, especially in the north of Vancouver Island and in the Strait of Georgia, where the residents follow the salmon. However, it is still unclear where these animals spend the winter. On the North American west coasts, there is also a good chance of encountering transients hunting for seals.

Orcas can be observed in Iceland in both summer and winter, although not quite as reliably as in Norway or North America. Another good place for orca watching is the Strait of Gibraltar in midsummer. They can also sometimes be spotted in Ireland, Scotland, Greenland or the Faroe Islands.

In the south, the Valdes Peninsula in Patagonia is particularly interesting, where transients are on the hunt for young seals and elephant seals directly on the beach in February and March. Orcas can also be regularly observed in the fjords of New Zealand's South Island.

The global population of orcas is unknown, but they are probably not acutely threatened with extinction and have been largely spared from whaling. It is estimated that there are around 50,000 animals. However, they are also endangered by whale-watching tourism, which is getting out of hand in many places, with too many operators crowding into too small a space and causing considerable disturbance to the animals – this is particularly true of the now inflationary diving with orcas.

If you find four, five or six different whale-watching providers in one harbour, it's probably better to look for another place.

Even more Whales

〰️

Even more Whales 〰️

Whaletrips Shop

The ideal Companion for your whale trip

All the whale facts you need while on the road – with plenty of space for own thoughts and observations!

Whaletrips Shop

Our Whales as Cards and Stickers

Colourful, finely illustrated, ready to stick on: Our whales are now available as stickers and greeting cards!

Whaletrips Shop

Beautiful whale Notebooks

Whether for travelling or at home: our high-quality whale notebooks come in five beautiful colours!

Whaletrips Shop

Our favourite photos for your home

Brightens any wall: a selection of our favourite motifs is available as elegant fine art print for your home.